DRC crisis needs more than a military solution

Given the history of its member states, Sadc should know better. The grievances of the Congolese people against their government must be addressed.

Image: REUTERS/Olivia Acland

At the beginning of 2019, Africa and the world hailed the first peaceful transfer of power between an outgoing and an incoming president in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Unfortunately the cheers were short-lived as President Félix Tshisekedi soon tore apart the agreement underlying the new political dispensation.

Since then, the situation in the DRC has gone from bad to worse. To a point where the country is close to imploding as a result of the civil war, which is threatening to destabilise the entire region.

If the crisis and its root causes are not properly addressed, efforts to end it will be in vain.

To restore peace and stability in eastern regions of the DRC, it is important to resolve the issue of national and foreign armed groups present on Congolese soil. However, contrary to what authorities in Kinshasa wish everybody to believe, the crisis is not limited to either the unconsidered actions of M23 — misleadingly presented as a group of anarchists, proxies of a foreign state without legitimate demands of their own — or to disagreements between two neighbouring countries, DRC and Rwanda.

The crisis in the DRC dates back to 2021 and is multidimensional. It is a security and humanitarian crisis, yet also — and more fundamentally so — a political, social, moral and ethical one. This aspect is minimised or even ignored by the DRC’s partner countries and organisations, Sadc included.

At a national level, the main cause and driving engine of this crisis is the clear and affirmed will of the current DRC leadership to break the Republican Pact. This agreement came from the inter-Congolese dialogue at Sun City, and resulted in a constitution adopted by popular referendum in 2006.

A true basis for national stability and cohesion, the pact — facilitated by former presidents Quett Masire of Botswana and Thabo Mbeki of South Africa — made it possible to end several years of civil war, to reunify the country, to hold three successful elections, and have the country experience the first peaceful transfer of power since independence.

The questioning of this Republican Pact first took the form of deliberate and recurring violations of the constitution and laws of the land. Then there were the sham elections of December 2023. These were held in violation of the legal framework and relevant international standards, which amplified the illegitimacy of the ruler, artificially reduced the weight of the political opposition and made the head of state the absolute master of the country. Tshisekedi also publicly announced his firm intention to change the constitution.

The negative consequences of this are staggering. It is a big democratic setback. The present regime has muzzled any form of political opposition. Intimidation, arbitrary arrest, summary and extrajudicial executions, as well as the forced exile of politicians, journalists and opinion leaders, including church leaders, are among the main characteristics of Tshisekedi’s governance.

Further, the country’s indebtedness — which was brought under control in 2010 — has soared again, raising concerns about its long-term solvency.

Any attempt to find a solution to this crisis that ignores its root causes — at the top of which lies the governance of the DRC by its current leadership — will not bring lasting peace. The innumerable violations of the constitution and human rights, as well as repeated massacres of the Congolese population by Tshisekedi’s police and military forces will not end after the successful conclusion of negotiations between the DRC and Rwanda, or the military defeat of M23.

Given the history of its member states, Sadc should know better. The grievances of the Congolese people against their government must and should be addressed. The persistence of the current bad governance of the country would certainly lead to new rounds of political turmoil, insecurity, institutional instability, armed conflict or even civil war.

The crisis requires a holistic solution — not solely the contribution of troops and military equipment. This amounts to wasting valuable resources in support of a dictatorship, instead of helping DRC to move towards democracy, peace and stability, and to become an asset for the southern African region and the continent.

The world is watching to see whether South Africa — known for its humanism and values — will continue to rush troops to the DRC to support a tyrannical regime, and fight the aspirations of the Congolese people.

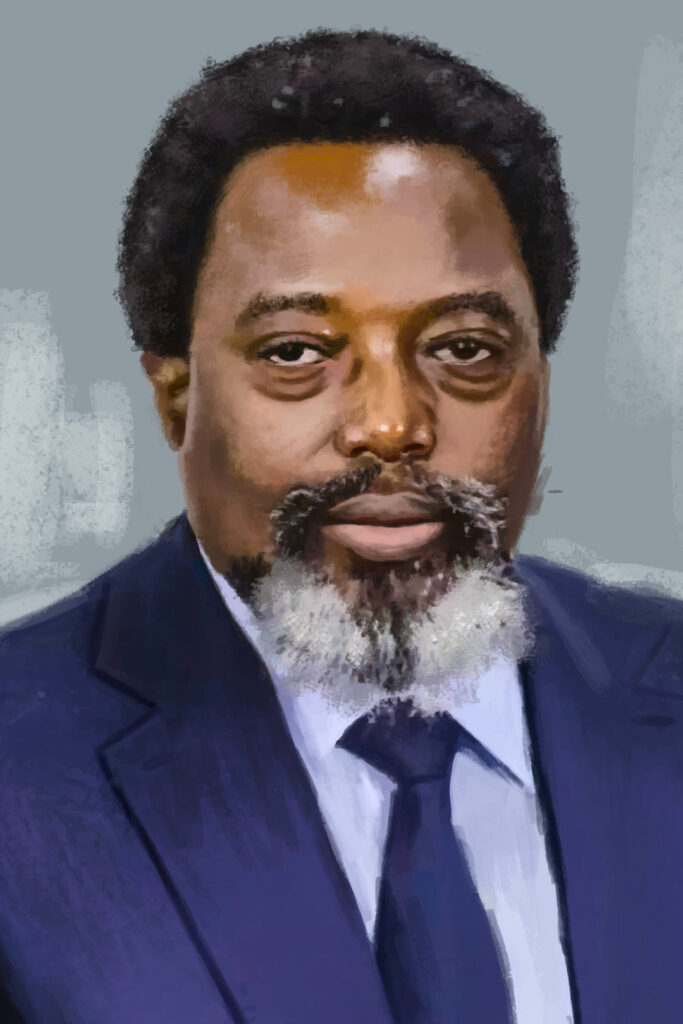

by Joseph KABILA KABANGE | Former President of the DRC

@JKabilaKabange

Original article published by https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/opinion-and-analysis/opinion/2025-02-23-drc-crisis-needs-more-than-a-military-solution/

Badinter, Kabila, Tshisekedi : la justice n’est pas la vengeance

Badinter, Kabila, Tshisekedi : la justice n’est pas la vengeance  Dominique Sakombi Inongo, quinze ans déjà : héritage vivant, avenir commun

Dominique Sakombi Inongo, quinze ans déjà : héritage vivant, avenir commun  Joseph Kabila Kabange ou l’incarnation de la stature, du silence et de la mémoire souveraine de l’État

Joseph Kabila Kabange ou l’incarnation de la stature, du silence et de la mémoire souveraine de l’État  En RDC, Joseph Kabila met Félix Tshisekedi en garde : « Tôt ou tard, la supercherie sera évidente pour tous »

En RDC, Joseph Kabila met Félix Tshisekedi en garde : « Tôt ou tard, la supercherie sera évidente pour tous »  RDC : l’opposition se dresse contre la peine de mort requise contre Joseph Kabila

RDC : l’opposition se dresse contre la peine de mort requise contre Joseph Kabila